New Work: Three Challenges to Protecting Millions of Young Egyptians.

2025-02-24

2025-02-24

Zeinab* is a brilliant 26-year-old girl who dropped out from her university studies because she could no longer afford it. She bounced between many low-skilled jobs in the retail sector, before settling on being an independent worker in the platform delivery sector.

For her, being self-employed freed her from the stigma of being a low skilled worker in a small business. It also gave her more freedom to choose the employers that best fit her conditions. Her primary concerns were to find workplaces withless exposure to workplace sexual harassment and having more flexible hours. “Unlike when I work in a secluded small shop with an employer, I feel more secure when I drop goods at the doorstep of a household, because my supervisor knows my whereabouts all the time. I can report any violence or harassment incidents”, she said.

Zeinab is one of many young people in Egypt with little capital except for access to a bicycle, motor bike or a smartphone who currently work in the delivery services and hail-riding apps. This emergence of this “New Work” or “platform work,” demands closer examination in order to understand the opportunities and challenges it creates for Egyptian workers.

While platform workers are able to compare and choose between different platforms depending on the rate and bonuses each one is offering to maximize their daily income, Zeinab expressed a common dissatisfaction with her job. While delivery platforms offer opportunities for employment, many of the well-known delivery online applications lack the basic social protection tools that should be offered to the workers they need for their platforms.

Examining Egypt’s Platform Work Landscape: A Closer Look at the FairWork Index

The Fair Work Index in Egypt tracked the performance of 7 platforms, according to five fair work criteria. Those criteria are developed in coordination with Oxford University. The criteria are: fair pay, fair contracts, fair working conditions, fair management and fair representation.

The best platform of the year 2021 (Platform in Service), in terms of fair work, received five out of ten. Then in 2022/2023, the second report was released, covering 10 platforms/companies. Three platforms received the best rating, 6 out of ten (Breadfast, Marsool, and Orcas), while Talabat, Uber and ElMenus received 4, 3 and 1 out of 10 respectively.

These ratings show the need for a wide discussion among all stakeholders on how to deliver fair work conditions without harming the growth and dynamism of these nascent businesses.

The question is: how do we improve working conditions?

A Multi-Stakeholder Approach to Fair Work

Motivated by its belief in the power of multi-stakeholder approaches to inclusive development, The Access to Knowledge for Development Center (A2K4D) mapped stakeholders working on social and economic justice and on labor rights in 2024. To meet this objective, A2K4D conducted several rounds of discussions and hosted a round table, gathering representatives of most of the stakeholders, with the exception of platform owners and managers who couldn’t make it to the round table. However, the perspective of platform owners and managers were collected through surveys by A2K4D staff. The aim of this initiative was to determine who are the key players needed to contribute to this nascent debate on how to improve the ranking of these platforms on the Fair Work Index without harming their business models.

The first discovery highlighted by the report was the lack of familiarity among CSOs about the Fair Work Index or work previously on protecting those working with platforms prior to being contacted by A2K4D though most expressed interest in protecting workers employed through platforms under informal labor conditions.Additionally, parliamentarians contacted were familiar with the subject, as the anticipate discussing amendments to the labor law by the Egyptian government. They perceived this moment as an opportunity to highlight the need to include this category of “new form of work” into regulations around social protection and minimum labor rights. The dominant concern expressed by NGOs and parliamentarians was centered around the process of advocating for the inclusion of these rights in the newly prepared labor law draft.

Second, legal help was offered to workers to amplify their voice and foster collective power for bargaining for better working conditions. Also, the example of platform workers was introduced as a case study in a regional training program for researchers on social protection.

Finally, a focus group discussion (FGD) gathered digital workers from the delivery sector, NGOs working on social justice, labor rights lawyers and researchers, trade unions representatives, parliamentarians, an ILO expert and a representative from the Social Security Fund. The objective was to develop recommendations on how to extend social protection to the different types of workers with digital platforms and especially how to enshrine their rights within the new labor law, currently under discussion in the House of Representatives. In other words, the focus group intended to answer the pivotal question: how do we create formal jobs in the platform economy. Based on this discussion a policy note with recommendations on how to include digital workers rights in the new labor law was produced and offered to a number of members in the Senate, the House of Representatives and the Presidency’s consultant, Hala ElSaid.

Three Challenges

There are three challenges that the legislator should pay attention to in terms of providing social protection for new forms of work of all kinds. These challenges are:

They are challenges are interrelated and are critical to ensuring social insurance covers all types of workers across platforms, whether through “cloud work” or “ground work”. Such challenges should be tackled by the government, and negotiated in close collaboration with business leaders, to ensure that workers employed through digital platforms and all forms of new work can enjoy decent work standards. Addressing these challenges can ensure that the benefits of the digital economy are maintained without compounding the negative impact on the MENA region’s working poor.

I believe that if this opportunity is missed, this growing business model could ultimately constitute a burden on the government, hinder comprehensive development, and create a gap between growth and the sustainable development goals as defined by Egypt's 2030 strategy.

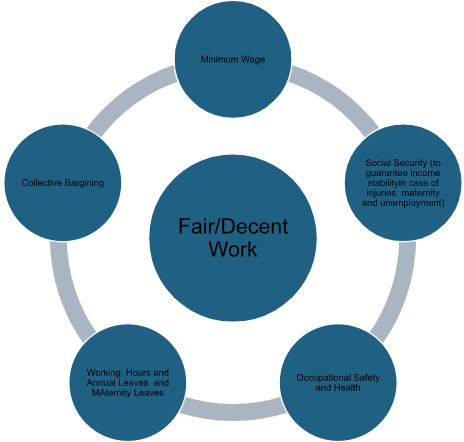

The figure below shows the most relevant decent work criteria that should be made available for digital workers, based on the outcomes of the FGD. Many of them could be matched with the five criteria studied under the Fair Work Index.

The Gender Tax

Yet while the challenges listed above are shared by all workers, applying an intersectional examination of the conditions faced by female workers exposes an even harsher reality. Not only are women more likely to be exposed to harassment and physical danger on the job, women’s care work also often adds an additional burden.

When we spoke with Zeinab, she reflected that while she currently does not suffer from this particular issue, she knows that having children would prevent her from continuing this job. She also highlighted that her male colleagues who support their families, are all heavily indebted and are unable to find other jobs.

Even if the law recognizes this form of work and gives the workers the right to prove their work relation with a certain platform, there is still a long way and hard negotiations for the platforms to improve their ranking on the Fair Work Index. The more and better-informed stakeholders are involved to make this shift, the better results are attained.

*Zeinab is not her real name. It has been concealed for privacy purposes.

By: Salma Hussein is an Independent Consultant at Al-Ahram Establishment and a researcher specializing in macroeconomics, labor, and budget policies.